Washington, D.C. – Ambassador Beth Van Schaack, the seasoned diplomat and point advisor to the US Secretary of State on issues related to war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide, has embarked on her second trip to Liberia within five months. Her visit coincides with a pivotal moment as she engages with key stakeholders to address the legacy of the country’s devastating civil war.

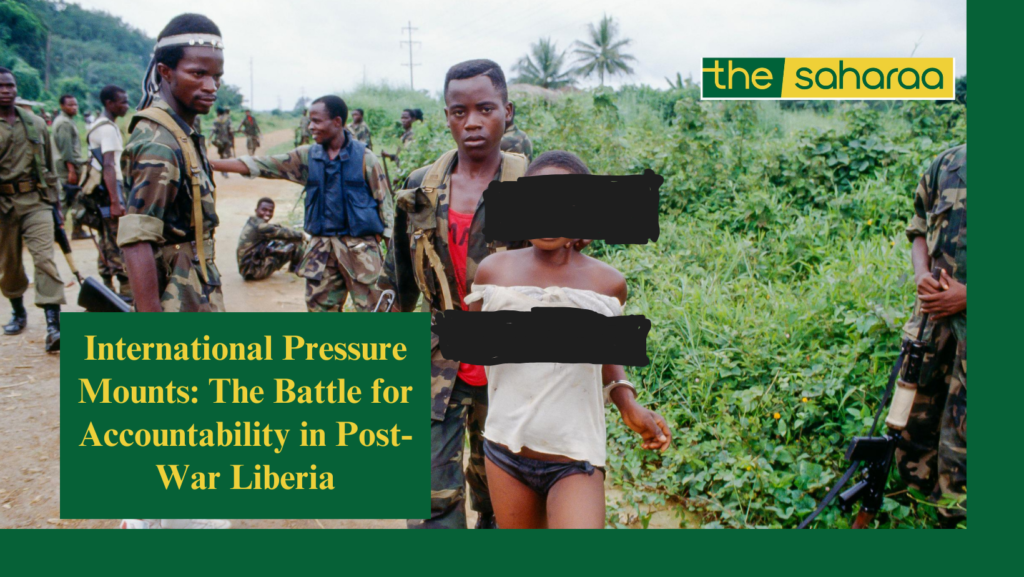

Ambassador Van Schaack arrives in Monrovia with a weighty agenda. Her focus is to engage in dialogue with Liberian leaders, survivors, and lawmakers on the establishment of a War and Economic Crimes Court (WECC). Ambassador Van Schaack carries the hopes of a nation healing from trauma. The establishment of the WECC represents a critical step toward reconciliation and justice for the estimated 150,000 lives lost during Liberia’s dark chapter of violence, rape, and forced recruitment of child soldiers. It will represent a critical step towards healing and accountability for a nation scarred by its past. Liberia, scarred by a brutal civil war that spanned several years, now stands on the precipice of a significant turning point. The establishment of a War and Economic Crimes Court looms large, and Ambassador Van Schaack’s role in this process is pivotal.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), which concluded its work in December 2009, holds vital insights into Liberia’s troubled past. Its final report contains a comprehensive analysis of the conflict, including root causes, impact on various segments of society, and responsibility for gross human rights violations. Among the TRC’s recommendations are strategies to address war crimes and atrocities committed during the war.

Ambassador Van Schaack emphasizes the importance of heeding these recommendations. “It is never too late to dispense justice,” she asserts. “The individuals who suffered these crimes continue to call for justice, and those in positions of power must carefully consider the TRC’s findings.”

Liberia’s Painful Past

Liberia’s civil war began in 1989, leaving scars that still resonate today. While most violence subsided by 1997, renewed clashes in 2003 drew international attention. The conflict claimed an estimated 150,000 lives, affecting one in twenty Liberians. Civilians endured widespread violence, including killings and rape, while child soldiers were forcibly recruited into armed groups.

In 1989, Charles Taylor spearheaded an incursion from the northeast, igniting what would become Liberia’s brutal civil war. Taylor skillfully cultivated external alliances with Burkina Faso, Libya, and Côte d’Ivoire, while internally, his support base primarily consisted of Gios and Manos. Within months, fractures emerged within the rebel movement. The Independent National Patriotic Front of Liberia (INPFL) split from Taylor’s National Patriotic Front of Liberia (NPFL). In a shocking turn of events, the INPFL assassinated President Samuel Doe in 1990, but the conflict persisted, pitting Doe’s Armed Forces of Liberia (AFL) against the NPFL and the INPFL.

This year marks 21 years since the end of Liberia’s civil wars through the Accra Comprehensive Peace Agreement. Yet, criminal accountability remains elusive within the country’s borders. Notable cases have been prosecuted abroad, including the US federal conviction of Charles Chuckie Taylor, Jr. for torture committed in Liberia. Additionally, former rebel commanders Alieu Kosiah (in Switzerland) and Kunti Kamara (in France) faced justice for crimes during Liberia’s first civil war. Meanwhile, a pending case in Belgium underscores the global effort to hold perpetrators accountable.

The Venue: Accra, Ghana

Amidst renewed interest from the United States, reports indicate that Ghana is being considered as the venue for Liberia’s long-awaited War and Economic Crimes Court. International stakeholders advocating for a war and economic crimes court are wary of potential protests in favor of some of the accused if the trial were held in Liberia. Additionally, there are concerns about the economic benefits—with Ghana potentially having an advantage over Liberia in terms of donor funds. The delicate balance between justice, practicality, and economic consideration remains a critical point of discussion.

However, this proposal has sparked reservations, particularly from Cllr. Jerome Verdier, the former head of Liberia’s erstwhile Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Cllr. Jerome Verdier, now an advocate for the war crimes court based in the United States, in a recent appearance on OK FM, Cllr. Verdier expressed concern that establishing the court outside Liberia would deprive Liberians of the social and economic benefits associated with such a tribunal. “Liberians should have the benefit of seeing justice,” Cllr. Verdier asserted. “The economic benefits, the healing and recovery process—all of these should take place within Liberia.” He emphasized that witnessing justice being served on their soil is crucial for the healing and recovery process. According to him, the court’s establishment should ideally take place within Liberia itself.

Diplomatic Tensions

In 2012, George Boley, accused of involvement in the recruitment and use of child soldiers during Liberia’s civil war, was deported from the United States to his homeland. Until the last elections, Boley held a seat in the lower house of the national legislature. However, his recent electoral defeat leaves him vulnerable, no longer shielded from potential accountability.

In a statement dating back to 2021, Secretary of State Anthony Blinken emphasized the importance of justice, the rule of law, and accountability for mass atrocities. These principles are not only moral imperatives but also vital to US national security interests. Engaging with the global community to address contemporary challenges remains a cornerstone of US foreign policy.

Secretary Blinken drew parallels to the historic Nuremberg and Tokyo Tribunals after World War II. US leadership ensured that fair judgments were permanently recorded against rightfully convicted defendants—from the Balkans to Cambodia, Rwanda, and beyond. Building on this legacy, the US continues to support international, regional, and domestic tribunals, as well as investigative mechanisms in conflict zones like Iraq, Syria, and Burma. The promise of justice for victims of atrocities remains steadfast, even when pursued cooperatively across borders.

Prince Johnson: A Controversial Figure

The absence of accountability for war crimes casts a long shadow over Liberia, exacerbating the nation’s current challenges. A prominent figure at the center of this complex web is former warlord Prince Johnson, whose actions during the civil war continue to reverberate. Senator Johnson’s legacy is marred by allegations of human rights violations and involvement in corruption. His role in the killing of former Liberian President Samuel Doe and other prominent figures remains a dark chapter in Liberia’s history. The Truth and Reconciliation Report explicitly implicates him in atrocities committed during the country’s initial civil war.

In December 2021, the United States took decisive action against Senator Johnson. As the former Chairman of the Senate Committee on National Security, Defense, Intelligence, and Veteran Affairs, he faced sanctions for his actions. The charges against him are multifaceted:

- Pay-for-Play Funding: Johnson allegedly engaged in a pay-for-play funding scheme with Liberian government ministries and organizations. Millions of US dollars were laundered, benefiting involved participants. Additionally, Johnson received an undeserved salary as a salaried intelligence “source,” despite providing no actual intelligence reporting to the government. His compensation was ostensibly tied to maintaining domestic stability.

- Vote Sale: Johnson reportedly offered to sell votes in multiple Liberian elections in exchange for financial gain.

Senator Johnson’s actions fall squarely within the scope of Executive Order 13818. As a foreign person who is a current or former government official, he is deemed responsible for or complicit in corruption. This includes misappropriation of state assets, expropriation of private assets for personal gain, and involvement in corrupt government contracts or natural resource extraction.

The Unresolved Challenge

As Liberia grapples with its legacy, the pursuit of justice remains a critical endeavor. The US’s unwavering commitment to accountability serves as a beacon of hope for a nation healing from its scars. In 2018, the US House of Representatives took a decisive step in support of criminal accountability. Recognizing the importance of justice and transparency, they underscored the need to hold perpetrators responsible for their actions during Liberia’s tumultuous past.

The shifting stance of the US Embassy in Monrovia regarding Liberia’s war crimes court has sparked controversy and raised questions about accountability and justice. Representative Jim McGovern (Democrat, Massachusetts) recently highlighted the urgency of addressing past atrocities during a Congressional hearing on Liberia.

The lingering problem lies in the failure to prosecute individuals identified by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). Many of those implicated in human rights violations continue to hold high-level government positions. Representative McGovern emphasized that accountability is not about vengeance; it is about fulfilling the rights of victims and ensuring justice prevails.

The US Embassy faced criticism from Human Rights Watch (HRW) in 2021. HRW pointed out that embassy personnel conveyed doubts about widespread support for a war crimes court in Liberia. Their reasoning? Liberians often prioritize securing basic needs over justice. This perspective undermines the nation’s aspirations for accountability and dismisses years of demands for justice across various sectors.

While resolutions have been passed, the US Embassy’s position remains cautious. Staff members indicated that expressing support for a war crimes court would require a clear request from the Liberian government.

While the US has consistently advocated for justice in various African nations, Liberia’s situation remains complex. Consider the following instances:

- Guinea: The US urged Guinea to address crimes committed during the 2009 stadium massacre.

- Democratic Republic of Congo: Calls were made for the prosecution of numerous rapes committed in 2012.

- South Sudan: The establishment of a hybrid court to try atrocities during the civil war was encouraged.

- Sierra Leone: Former Liberian President Charles Taylor faced trial for crimes related to Sierra Leone’s civil war before a UN-backed court.

- Senegal: The Extraordinary African Chambers were established to try serious crimes committed by former Chadian dictator Hissène Habré.

- Central African Republic: The Special Criminal Court was established to combat impunity.

In contrast, Liberia grapples with unresolved accountability challenges. Despite cross-sectoral demands for justice, the US Embassy in Monrovia expressed reservations. Officials suggested that Liberians’ focus on daily needs might overshadow support for a war crimes court. However, this assumption overlooks the nation’s deep-rooted desire for justice.

As Liberia navigates its path toward reconciliation, the US’s role remains pivotal. Balancing immediate needs with long-term accountability is a delicate task—one that echoes across the continent.

President Boakai’s Decision

The final decision rests with President Joseph Boakai. While he has expressed willingness to support the establishment of the court, diplomatic sources reveal growing frustration over his pace in pushing for its realization. The signing of an executive order remains uncertain, leaving observers eager to see how this critical chapter in Liberia’s history unfolds.

In a recent interview with war crimes advocate Allan White, President Joseph Boakai expressed his endorsement for the establishment of a war and economic crimes court in Liberia. His statements underscore the urgent need for truth and accountability regarding the devastating civil conflict that scarred the nation.

President Boakai emphasized that Liberians deserve to know the unvarnished truth about the 14-year brutal fratricidal conflict that claimed hundreds of thousands of lives and displaced countless others. The war, which began in 1989, left deep wounds in the fabric of Liberian society. Impunity, disrespect for justice, and disregard for human rights have haunted the nation for far too long.

“In every country, especially one that has celebrated 176 years of independence,” President Boakai asserted, “we must confront our past. Let all the facts come to light. Innocence or guilt should be proven, allowing us to move forward as a nation. This is not a witch-hunt; it’s a matter of testifying to the truth.”

The President acknowledged that many individuals who participated in the civil war recognize the importance of transparency. Regardless of their allegiances during the conflict, they share a common desire for the truth to emerge. “The truth is truth,” President Boakai affirmed. “Each person has been affected, and we should find solace in finally closing this painful chapter of our history.”

During his inaugural address in January, President Boakai made a resounding commitment. “We have decided to set up an office to explore the feasibility of the establishment of the War and Economic Crimes Court (WECC),” he declared. The court aims to hold accountable those who bear the greatest responsibility for war crimes and crimes against humanity. It is a step toward closure, reconciliation, and justice.

As Liberia navigates this delicate terrain, the world watches closely. The pursuit of truth and accountability is both a national imperative and a global concern. The question remains: Will the means—through the establishment of the court—ultimately justify the end? Only time will reveal the answer.