By David Dueh Chieh Sr. (Private Secretary to the President)

There were no ominous signs regarding the President’s June 1971 trip to London for his annual medical treatment. However, circumstances necessitated a change in the mode of travel – instead of the usual ocean trip, it was by a Swiss Air flight. On the President’s entourage for the first time was Liberia’s Ambassador-at-Large, Mr. Emmett Harmon. Again, there was no premonition of any kind that the President’s trip to London for a routine annual medical check-up would be a “trip of no return.”

The flight to London went smoothly. We landed safely at the Heathrow Airport and were met by the Liberian Ambassador, Dudley Lawrence, and his staff; and we were checked-in at the hotel.

The next morning, President Tubman went to the Good Health Clinic for his medical check-up with his London physician. After routine examination, the President returned to the hotel and thereafter, dictated a letter to me for his London physician, stating that he was in London for his usual annual medical check-up and not for any surgery. The tone of the letter implied that his London physician might have recommended surgery to the President during his routine examination.

At this stage, both the President’s Liberian physician Dr. Henrique Benson and his London counterpart, had persuaded the President to undergo prostate surgery.

Not satisfied with their recommendation, President Tubman directed the then Assistant Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Ernest Eastman, to immediately proceed to Germany and invite his German Physician to London for a second opinion. Two days later, his German physician arrived in London with Secretary Eastman. But before meeting with the president, he was briefed by his colleagues, the Liberian and London physicians about their recommendation for the surgery.

Finally, when the German physician met with President Tubman, he concurred with his colleagues opinion that the President should undergo the surgery.

As Private Secretary to the President, I was in close proximity and therefore privy to official and nonofficial correspondences, formal and informal conversations and discussions as well as serving as the gateway to anyone who came in to see the President.

Appointments were made through my office and carefully scrutinized and then scheduled. And my travels with the President without a secretary for those years was a deviation from policy but it kept me duly informed on his activities and schedules. The London trip was no exception.

It seems to me that the pressures on the President from his London, Liberian and German physicians to undergo the surgery was overwhelming. From office discussions, I also overheard that the First Lady, Mrs. Antoinette Tubman, who was also in London, did encourage him to give in to surgery.

The President also received a telegram from his eldest son, Senator William V S. Tubman Jr., who was in Liberia, urging him to “trust in God and accept surgery.” The President responded by stating that he had always trusted in God, and added, rather prophetically, that “when you shall have heard, it would have been all over.” My perspective on the President’s response to his son’s telegram reflected that he was deeply anguished by his eldest son’s absence from his side, especially when he needed someone to be his advocate at this crucial period in his life, rather than receiving a telegram. There was the possibility that he could intimate some confidential information to his son before the surgery.

The Chief of the Intelligence Agency in Monrovia had dispatched a coded message to the President’s Chief of Security, urging the President not to accept surgery because it would be counter-productive. However, the message was intercepted by the next ranking officer because the chief of security was at the time also hospitalized in due to illness.

The Chief of the Intelligence Agency had reportedly unearthed a plot to assassinate the president through his physician. In order to set the stage for such operation, they needed to get him in a vulnerable position such as when heavily sedated after surgery. This plot was allegedly sponsored by the supporters of vice president William R. Tolbert, Jr.

Having resigned himself to consistent pressures to undergo the surgery, the President went back to the Good Health Clinic on July 21st, and on July 22nd, underwent the prostate surgery which was performed by a specialist.

On a personal note, I had surgery at the same hospital in 1969 and it was very successful. In accordance with post-operative procedures, I was taken back to my ward for recuperation. Except where there are complications, a patient will be confined to the intensive care unit until his condition improves.

I considered the President’s surgery to be successful because, when I visited him at the hospital, he had already been transferred from the operating theater to his private ward to recuperate. He was heavily sedated and could not speak. Needless to say, if his condition was in a more complicated state, he would not have been transferred to his ward for recovery. His Liberian security personnel guarded the door to carefully monitor all who came in and went out. I sat silently in the ward just gazing at him until I finally felt it was time to leave.

When I returned to the hotel about an hour later, I joined the other members of the President’s delegation in praying for his final recovery. The news of the surgery was not announced to the Liberian public from the onset, but when seen as a success, I immediately dispatched a telegram to the Special Assistant to the President, Hon. Mai Padmore, in Monrovia on the outcome of the operation. The text of my telegram was then released to the press and there was great excitement among the people when they received the good news.

However, that news would be short-lived.

Shortly after, we received a telephone call from the hospital stating that the President had developed “some complications and died.” We were numb. This was unexpected news. The President had been transferred to his ward for recovery. I had just visited him and sensed no danger. No one had communicated to us any concerns of complications. I had even just sent the message to Liberia that the surgery was a success.

We were all shocked, petrified and grief-stricken.

After reality began to set in, many questions bombarded me. Why the pressure for the President to under-go surgery in the first place? What kind of medication was given earlier to weaken the President’s immune system and why? What was injected in the President that caused him to hemorrhage to death?

The next couple of weeks would bring more self questionings.

When the ruling hierarchy of the True Whig Party received the sad news of the President’s death, they immediately met and sought for the Vice President, William R. Tolbert Jr., to be sworn in, but he apparently was nowhere to be found.

It was then alleged that Mack Deshield, Secretary General of the True Whig Party, had requested that he be sworn in as president instead. Realistically though, Vice President Tolbert could not be found in Monrovia in the midst of all of these occurrences. It was also alleged again that he had been taken to an area in Bong County, Central Liberia to give the appearance that he was not a conspirator in the plot to assassinate President Tubman.

Later that evening, we received information in London that Vice President Tolbert had been brought back to the capital in a Volkswagen beetle driven by a police officer. Later, there would be many rumors regarding the Vice President’s absence, his late return to Monrovia and the manner of his return.

That evening, the tragic news about the President’s death was officially released in Monrovia.

News reports indicated that there was complete pandemonium – people running helter-skelter; some neglecting their purchases for the Independence Day celebrations which were to be held on July 26th, others abandoning their cars and running through the streets weeping aloud and some even rushing home to share the news and privately weep with their families.

There was no autopsy to determine the cause of death, but the First Lady, Mrs. Tubman, who had the right to authorize the autopsy, was indecisive. So, whatever has been written or reported as to the cause of the president’s death was never the result of an autopsy as there was none performed to determine the actual cause of death.

It was alleged that when the Chief of Intelligence got the news that the President had the surgery but did not survive, he also died under mysterious circumstances.

We, members of the late President’s entourage and other Liberians in London had earlier gone in droves to the Liberian Embassy for an early Liberia’s Independence Day reception, slipped into a spirit of mourning following the sad and unexpected news of the President’s death.

After a brief memorial service at the funeral home in London where the President’s body was embalmed, the President’s body, along with the wailing members of his entourage, were flown back to Liberia.

The flight back to Liberia was filled with mixed emotions. A trip that took about six hours appeared to have lasted forever. Some members of the late President’s delegation appeared more worried than others. Apparently, his death would yield varying outcomes for each individual.

When the plane landed at the Robertsfield International Airport after a six-hour flight, a multitude of mourners had gathered awaiting the arrival of the President’s body. The Methodist Bishop Stephen T Nagbe, received the body, and after a brief eulogy, it was transported to Monrovia in a motorcade.

Citizens lined the route from the Airport to the capital city, Monrovia. People, both young and old, were weeping and wailing along the highway as the hearse drove by.

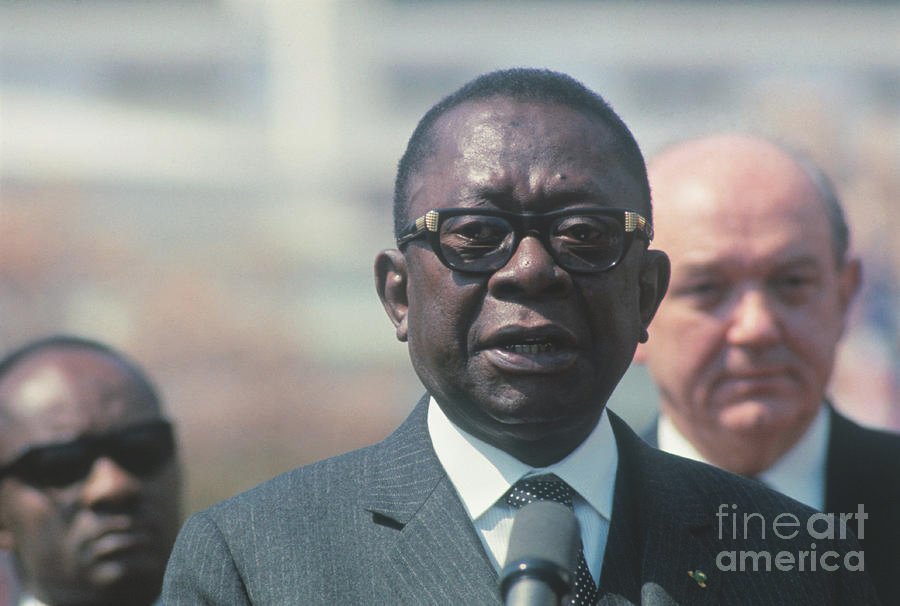

The funeral obsequies for the late President were performed at the Centennial Memorial Pavilion. It was attended by African Heads of State and Special Envoys from Britain, the United States of America and other European and African countries. Prominent amongst the African leaders who attended were:

- 1. Emperor Haile Selassie of Ethiopia

- 2. President Leopold Sedar Senghor of Senegal

- 3. President Siaka Probyn Stevens of Sierra Leone

- 4. President Ahmed Sekou Toure of Guinea

- 5. President Jean Bedel Bokassa of Central African Republic

- 6. President Moktar Ould Daddah of Mauritania

- 7. President Gnassingbe Eyadema of Togo

- 8. President Yakubu Gowon of Nigeria

- 9. President Felix Houphouet-Boigny of the Ivory Coast

- 10. President Kenneth David Kaunda of Zambia

- 11. President Jomo Kenyatta of Kenya

- 12. President Julius Kambarage Nyerere of Tanzania

- 13. President Muammar Al-Qaddafi of Libya

- 14. President Ahmadou Ahidjo of Cameroon

- 15. President Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire

- 16. President Abdelaziz Bouleflika of Algeria

- 17. President El Hadj Omar Bongo of Gabon

- 18. President Hosni Mubarak of Egypt

- 19. President Denis Sassou-Nguesso of the Republic of Congo

- 20. President Idi Amin Dada of Uganda

- 21. President Habib Bougubia of Tunisia.

The late President’s body was interred on the grounds of the Centennial Memorial Pavilion in Monrovia.

Transition To A New President.

In accordance with the Liberian Constitution, when a President dies in office, the Vice President succeeds him. With this stipulation, Vice President William R. Tolbert, Jr. was sworn in as the 19th President of Liberia on July 23, 1971.

Honoring The Late President’s Entourage.

Members of the late President’s staff who accompanied him on that fateful journey to London were later decorated with Liberian Orders by President William R. Tolbert, Jr., in the Parlors of the Executive Mansion.

I was decorated with the Humane Order of African Redemption. The Butler to the late President, Hon. Jimmy Barrolle, in his remarks before he was decorated, stated that the late President had planned, upon his return to the country, to embark on a farewell tour of the entire country, renewing acquaintances with the various Paramount, Clan and Town Chiefs. Upon his return to the capital, he would resign the office of President, thereby enabling the then Vice President, William R. Tolbert, Jr., to assume the leadership of the country according to Constitutional provisions.

Rumor mills had it that the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in America knew that President Tubman was assassinated instead of what was reported and that the Tolberts had something to do with it. As a result, they objected that Vice President Tolbert should become the President since he was part of the conspiracy. They instead contacted General Korboi Johnson, the Army Chief of Staff, to take over as president. General Johnson, who was still too shocked by the entire incident, declined as he knew that there were no provisions in the nation’s constitution to allow for such ascension of power.

The vice president was the legitimate heir to the presidency in the event that the President became incapacitated.